Kala Wewa: The Ancient Marvel of Sri Lankan Irrigation

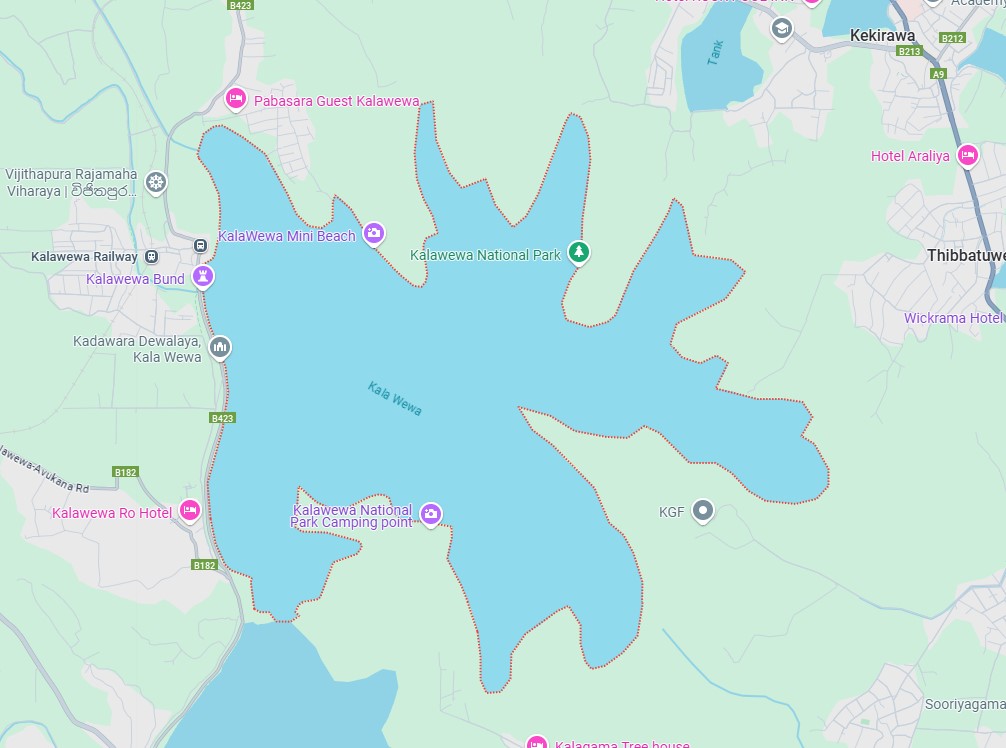

Kala Wewa is Sri Lanka’s most renowned and historically significant reservoir. Constructed during the reign of King Dhatusena in the 5th century CE, this gigantic man-made reservoir is an icon of intelligence and refinement of ancient Sri Lankan hydraulic civilization. In the North Central Province of Anuradhapura, Kala Wewa was not only an engineering marvel to meet the island’s water and agricultural requirements but also a symbol of sustainability that has stood the test of time.

Historical Background

King Dhatusena reigned between 455 and 473 CE and was an innovative king in Sri Lanka’s Anuradhapura Kingdom. Comprehending the significance of a secure supply of water to agriculture in the arid region, he directed the construction of Kala Wewa in 460 CE. Kala Wewa formed part of a huge system of irrigation, as detailed in the ancient chronicle, the Mahavamsa, which finally carried water through the Yoda Ela (or Jaya Ganga) to the city of Anuradhapura to support its inhabitants and its agricultural lands.

The construction of Kala Wewa at this time was a titanic project. It required enormous manual labor and engineering skills with minimal technology at hand. King Dhatusena’s doggedness with the project also tells of his care for the welfare and prosperity of his people. The reservoir, upon completion, was 40 feet deep and boasted a circumference of about 40 miles and was hence one of the greatest and most ambitious irrigation works of its time.

Engineering Achievement

The engineering and construction of Kala Wewa awe modern hydrologists and archaeologists. Spanning over 6,500 acres at its full capacity, its water storage capacity is approximately 123 million cubic meters. The bund, or the embankment, is approximately 22 kilometers long and is made up of earth, cleverly compacted to withstand the pressure of the water stored.

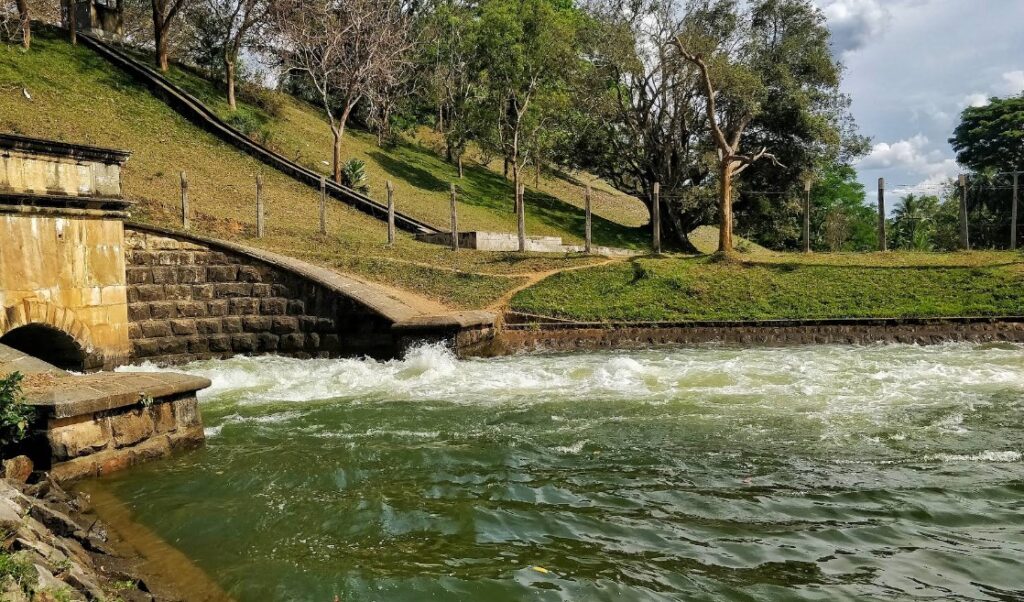

Maybe the most remarkable aspect of the Kala Wewa system is its connection with the Yoda Ela canal. The canal, running a distance of around 87 kilometers, was built with a gradient of just six inches per mile, a true marvel of ancient survey work and engineering. This gradient allowed for water to flow smoothly from Kala Wewa to Anuradhapura without clogging up or spilling over. This degree of precision in hydraulic design was rare in ancient periods and is an indication of how advanced the level of understanding of hydrodynamics was among Sri Lankan engineers then.

Agricultural Importance

It was Kala Wewa that played a pivotal role in the development of agriculture in Sri Lanka’s dry zone. This land, prone to drought and capricious rain, needed a consistent supply of water to nourish the crops and ensure food supplies. With Kala Wewa, irrigation of thousands of hectares of arable land would be feasible for the entire year, allowing for several cycles of crops and the growing of rice, vegetables, and other produce.

The reservoir was not only a water source but part of a magnificent, unified system of tanks and canals known as the tank cascade system. This meant that any excess water from one reservoir would overflow to the next, conserving wastage and maximizing utility. Even today, remnants of this ancient water management system are used and studied for implementation in sustainable water use.

Cultural and Religious Significance

Kala Wewa is not only an engineering feat but a site of cultural as well as religious importance. The famous Avukana Buddha image, attributed to have been carved around the same time under the patronage of King Dhatusena too, is found close to the reservoir, according to historical accounts. The Avukana Buddha, which stands well over 40 feet tall, faces the Kala Wewa symbol, indicating the conciliatory co-existence of spiritual existence and agro-prosperity in ancient Sri Lankan society.

Also, the reservoir and the surrounding area are laden with folklore and legends. One of these stories states that King Dhatusena met a tragic end at the hands of his own son Kashyapa because Kashyapa wished to know the king’s treasure secret. The king, before his death, gestured towards Kala Wewa and said, “This is all the wealth I have.” The tale illustrates how the king believed that the reservoir, which gave him nourishment and life to his people, was his most prized possession.

Modern Relevance

Today, Kala Wewa is still a vital source of water for irrigation, for drinking purposes, and for hydroelectric power in the region. It has been integrated into the Mahaweli Development Project, which is one of Sri Lanka’s largest irrigation schemes, helping to distribute more efficient quantities of water to the north and east of the country.

There have also been efforts to restore and rehabilitate portions of the reservoir and connected canals, recognizing them as being of historical as well as utilitarian significance. Environmentalists and policy makers see Kala Wewa as a model for all future water resource sustainability, particularly in light of climate change and increased water scarcity.

Furthermore, the site has drawn tourists and scientists alike. Coupled with the proximity of the Avukana Buddha and the peaceful nature of the reservoir itself, Kala Wewa is half historical site and half natural haven, contributing to Sri Lanka’s cultural tourism industry.

Ecological Role

Kala Wewa is also significant in the regional ecosystem. It is home to a diverse group of flora and fauna, including migratory birds, freshwater, and endemic species. The wetland created by the reservoir aids in the conservation of biodiversity and harbors habitats required for ecological balance.

The forested catchment and surrounding areas play a crucial role in maintaining the health of the reservoir. Deforestation and pollution are critical concerns to the integrity of the water system, with increased conservation efforts resulting from these challenges. Consistent efforts by government and community programs focused on sustainable practices and environmental awareness are meant to protect Kala Wewa and its area for future generations.

Kala Wewa is a lasting testament to the brilliance of the ancient Sri Lankan engineering and wisdom of a king obsessed with sustainable development. Over 1,500 years since its construction, the reservoir continues to nourish the land and the people, linking the past to the present. It is a not only a practical achievement in water management but also a spiritual, cultural, and ecological expression of Sri Lankan civilization. While the world looks for sustainable solutions to today’s challenges, Kala Wewa provides a convincing testimony of how innovation and tradition may peacefully coexist in the interest of human and nature.

From Colombo to Kala Wewa

By Public Transport:

- Train , Bus

- Take a train from Colombo Fort to Kekirawa (around 4.5–5.5 hours).

- Trains on the Northern Line (Colombo–Jaffna or Colombo–Vavuniya) stop at Kekirawa.

- From Kekirawa town, take a local bus or tuk-tuk to Kala Wewa (about 10–15 km).

- Take a train from Colombo Fort to Kekirawa (around 4.5–5.5 hours).

- Direct Bus

- Take an intercity bus to Anuradhapura or Kekirawa (Route No. 15).

- From Kekirawa, use a local bus or tuk-tuk to reach Kala Wewa.

By Car/Taxi (Private Transport):

- Drive via A6 (Colombo–Trincomalee Highway) or A9 (Kandy–Jaffna Road).

- Estimated time: 4.5–5 hours.

- Set your destination as “Kala Wewa Reservoir” or “Avukana Buddha Statue” on Google Maps — Kala Wewa is nearby.

From Kandy to Kala Wewa

- Distance: 100 km.

- Route: Kandy → Dambulla → Kekirawa → Kala Wewa.

- Time: Around 2.5–3 hours by car.

Points of Interest Nearby

- Avukana Buddha Statue – a famous ancient rock-carved Buddha statue near Kala Wewa.

- Kekirawa Town – nearest town for accommodation, food, and transport.

- Yoda Ela (Jaya Ganga) – ancient canal connected to Kala Wewa.

- Ritigala Forest Monastery – an ancient Buddhist site, about 30–40 minutes away.